A question I receive very, very often asks ‘what are model releases?’ accompanied, usually, with a plaintive ‘Do I really have to get them signed?’

The answers are: ‘They’re not things to mess with’. and ‘Yes!’ Here’s the clearest possible example of what can go wrong.

A photographer who failed to obtain a model release could cost her agency, Getty Images, a six-figure sum in damages (no joke: the claim was $450,000 and she was awarded $125,000).

The basic facts are plain and agreed: the photographer made a portrait of a pretty young lady, submitted it to Getty and claimed that she had obtained a model release for the image. Next thing the young lady learns of the image is a message on Facebook saying she’s in an ad which seems to say she’s HIV-positive.

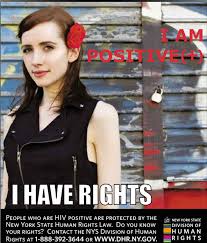

Immediately, according to court papers she ‘“became instantly upset and apprehensive that her relatives, potential romantic partners, clients, as well as bosses and supervisors might have seen the advertisement.” For the lady says she is not HIV-positive. The image from the ad published in April 2013 is shown above. The photographer, Jena Cumbo, says she ‘made a mistake’. Some mistake. Getty Contributor guidelines are as clear as can be about the need to say whether the images are released or not.

So what to do?

What does it mean for the ordinary photographer? Broadly, roughly speaking, the safe ground for photographs of people who are identifiable is when they are used editorially. For example, the reporting of news or current affairs or appearing in general magazine features in which the person or persons have not been directed for photography and who have not expressed any objection to being photographed. For these uses you can get away without a model release. … most of the time. You had better be sure the caption information is accurate however. If you suggest, as happened in one classic case, that a man’s female companion was a lady of the night (in fact it was his daughter), you’ll be in trouble, and serve you right. And you need to be careful if you’re photographing on private property with permission as conditions may attach to that permission. And photographing in a public space is no defence, particularly if the subject is on private property but maybe even if not.

Get the idea? It’s a sticky world out there.

All other situations – in which you direct someone, or you’ve been asked to photograph someone (including weddings, social, events photograph) – you’d jolly well get a model release if you wish to publish the photograph anywhere. And that means in any general medium accessible by the public such as Facebook, Flickr and other photo-sharing sites. And if you wish to use a photograph for advertising, irrespective of how you obtain the photograph, you absolutely must obtain a model release first.

By the way in many jurisdictions, a model release is a property transaction which needs a material consideration (in plain English: payment of some kind) to be enforceable i.e. so you can rely on it as a defence. That payment can be any form, from a stick of gum to a signed print, a CD of images or cash payment. (Look up the sad but instructive story of Robert Doisneau’s ‘The Kiss’ in my ‘Photography – the definitive visual history‘.)

With mobile apps that make it easy to sign off model releases there are no excuses for being sloppy about obtaining them. Especially if you’re a pro supplying a pro agency.

Go forth, and get your model releases (and keep them safe)!

Further reading: Report from Arthur Leonard, New York Law School